First published on the Create50 Blog, 16 July 2015

0 Commentaires

I’m always astonished when I read the vitriol anonymous commentators hurl at complete strangers in the guise of “criticism”. Alas, a handful of comments left on the BBC website in response to Tony Jordan’s latest drama, “The Ark”, were typical of this hyperbolic bile that daily floods the Internet. Normally, I try not to let gratuitous incivility get to me. This time I feel I have to speak up, because the comments revealed assumptions about “Drama” that I couldn’t leave unanswered.

1. Mythology is not a suitable topic for Drama I know, I know. I too find it totally bizarre that an armchair critic would complain about using a myth or legend as the basis of a screen story. After all, some of the most memorable films of all time re-tell ancient myths. From Jason and the Argonauts to King Arthur and his knights of the round table, mythology has been a staple of filmic fare since… well, since films began. Perhaps they were just objecting to the depiction of a BIBLICAL legend? I’ve got a riposte for that one as well. The story of the flood was first recorded not by the Hebrews, but by the ancient Sumerians in “The Epic of Gilead”. It’s a great read – I recommend it. Different names, a smaller boat and a more localised flood, but the same story. That some cataclysmic event really did occur in the Bronze Age, leaving a lasting impression on human consciousness, is highly probable. Why wouldn’t this be a suitable topic for a film? What makes a suitable subject for a film? ANYTHING! As long as the writer has the skill to tell a story that reveals some truth about the human condition through characters and their conflicts in a psychologically satisfying structure - usually three acts presenting thesis, antithesis and synthesis - the actual story can be about absolutely anything. 2. Faith is not a suitable topic for Drama Some armchair critics lambasted the BBC for using licence-fee money to fund a drama that did not advance the atheist agenda. Others claimed that because “The Ark” depicted a central character whose belief system was different to theirs, the BBC was guilty of peddling propaganda. My goodness. What astonishing bigotry! Surely in this day and age we’re open-minded enough to accept all belief systems and not just the West’s politically correct/ intellectually fashionable atheism? Evidently not. Atheism too has its Pharisees. Personally I found it refreshing to see a man of faith depicted. Most characters we see in drama these days are cynics, agnostics or atheists. More to the point, in “The Ark” the protagonist’s faith was germane to the action. It provided the motivation for the character to build a big boat in the desert 70 miles from the sea against the wishes of his family. As far as dramatic set-ups go, that’s as near to perfection as you will find. 3. Old stories shouldn’t contain contemporary elements OK. I’m putting my hand up here and freely admitting: I’m a bit of an iconoclast. When I was twelve, I re-wrote “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” in “proper” English. I don’t object when Shakespeare plays are set in an era other than Elizabethan. My DVD collection contains four versions of Hamlet, all with different historical settings… When it came to “The Ark”, armchair critics moaned about Nico Mirallegro’s short haircut. Perhaps they know something I don’t? Maybe they have some sort of psychic connection with a Bronze Age hairdresser who has told them categorically that not a single man alive at that time kept his hair short? Somehow I doubt it. The town fleshpot where teens danced to pounding music, snogged and smoked mind-altering substances also didn’t go down well. “People were shown smoking before smoking was invented!” exclaimed one armchair critic. Well, yes, smoking tobacco wasn’t prevalent in the West until Sir Walter Raleigh introduced the ugly habit in Elizabethan times, but who’s to say people weren’t smoking other narcotics elsewhere on the planet long before then? Can anyone seriously claim that teenage angst was invented in the 1950s? Where’s the evidence that teens of the ancient world were less likely than their modern peers to be driven to disastrous life-choices by their raging hormones? While authenticity was clearly a core production value, the look and feel of the film was ultimately an interpretation. Most of what we think we “know” about the Bronze Age is conjecture. Archaeologists revise their theories all the time. Quite frankly, these quibbles miss the point. By giving the story a contemporary feel, Tony Jordan’s aim was to make it more accessible to the audience. I thought he brought it off beautifully. 4. Drama should be based on facts Perhaps it’s the proliferation of docu-dramas that has folk confused, but it’s documentaries not dramas that should be based on facts. Drama is fiction, or in the case of biopics or historical dramas, a fictionalised account of facts that may tell a few lies to tell a better truth. Sometimes, for example, a screenwriter may need to compound several characters into one or play with chronology in order to make the story work. As Horace said, the purpose of drama is not only to instruct, but also to delight. That’s not to say drama should be casual with historical facts. I still haven’t forgiven the makers of “U-571” for the disrespect they showed to the British servicemen who sacrificed their lives to capture a German Enigma machine during World War Two by changing their nationality. Anyone who has read history will know the Americans hadn’t even entered World War Two when the crew of H.M.S. Bulldog did that… I’ll never watch another film by that writer/director ever again! Where possible then, a drama should respect historical facts, or at least remain true to their spirit. A story should have an internal logic and obey the rules of the world it sets up, otherwise it will lack credibility. It may sound like I’ve just contradicted myself, but really, there was no good reason in the story world of U-571 why the writer/director couldn’t stick to the historical facts and have the protagonists be British. It wasn’t “a better truth” he told with his lie… It's a thin line. Back to “The Ark” - why did it provoke such venomous comments? I blame the Dawkins Delusion. Richard Dawkins claimed to have disproved the existence of God. I for one would have been happier had he succeeded. It’s so much easier not to have to love your neighbour as yourself, isn’t it? Unfortunately Dawkins’ argument is spurious. He says God doesn’t exist because (a) organised religions often behave badly and (b) the probability s/he exists is small. As a woman, I wholeheartedly agree organised religion has not always been a force for good. In Western culture half of the population was enslaved to the other half for centuries, justified by the teaching of the Catholic Church. The irony is, the Catholic Church based its dogma not on the preaching of Christ, but on the secular speculations of Aristotle who didn’t know women had sex organs (because ours are internal) and so assumed we must be inferior to men. Religions are set up by men, not by God. If they have shortcomings, mankind and mankind alone is to blame. Assuming for one moment there is an afterlife, any woman wanting to administer a short, sharp kick in the balls to Aristotle will have to get in line… behind me. Turning now to the probability argument. You’ve only got to have some rudimentary mathematics - or else read Nassim Nicholas Taleb - to understand that just because something is improbable, it doesn’t mean it’s impossible. To borrow Taleb’s eloquent metaphor, for all you, Dawkins or I may know, God could be the ultimate “Black Swan Event”. Tony Jordan’s formulation was pertinent: only an idiot would say God doesn’t exist, because to be able to say that categorically, you’ve got to know everything, and none of us does. Rant over. Best get back to writing my own screenplays… “An epic tale of romance, revenge and cappuccino.” A brilliant tagline. Up there with the best, IMHO. Can you name the film? Here are some clues:

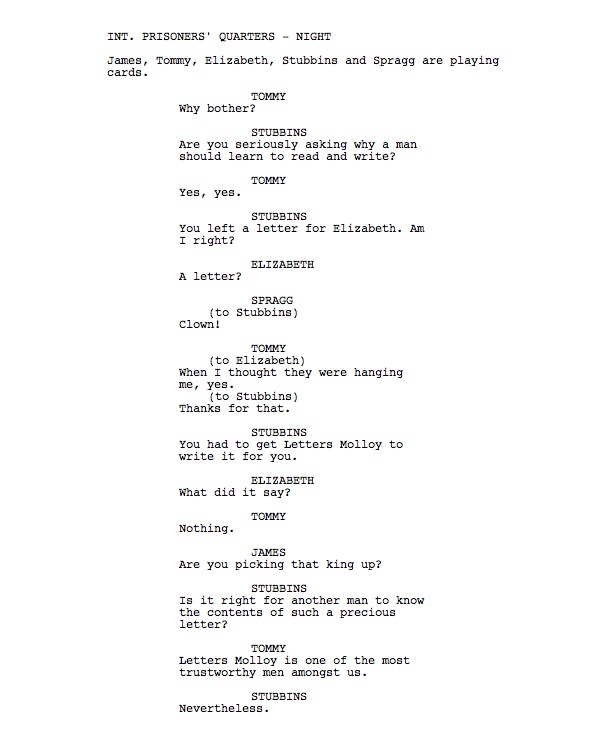

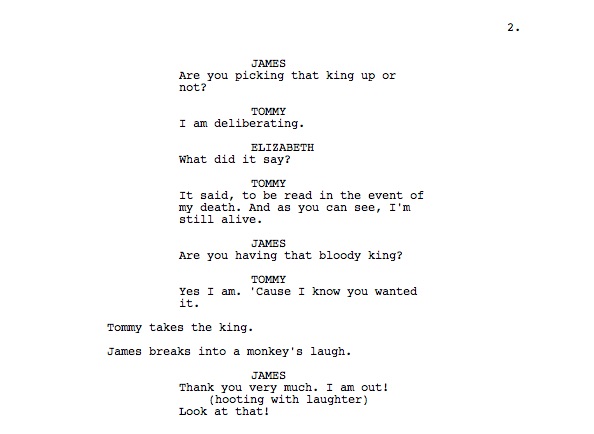

With that sort of praise, you might think “Queen of Hearts” was a landmark British cinematic event that has taken its rightful place as one of this eclectic nation’s best-loved films. But you’d be wrong. Nobody even knows where the negative is! So when the email came through inviting me along to the Barbican to watch “Queen of Hearts” in the company of Tony Grisoni and actors Joseph Long (Danilo Luca), Ray Marioni (Mario) and Tat Whalley (Beetle), I couldn’t resist. Here are seven writing tips I came away with: 1. Passion Tony Grisoni sat down to write a film he wanted to see. Not a film he thought would sell. Not a bland, “me-too” film he thought was safe. A film with a great story he wanted to see himself. And the passion shows. 2. Authenticity Versus Autobiography The Luca family feels so authentic, lots of audience members mistakenly believe this must be Tony’s autobiography. That authenticity may derive in part from his experiences as a Brit of Italian extraction informing the story, but it is a false biography. Credit must go to the actors too, of course. When you watch the performances, you can’t imagine any other actor playing those parts. Joseph Long, who plays happy-go-lucky Danilo Luca in the film, explained that Jon Amiel helped the actors to really inhabit their character by improvising the scenes that might have happened before the scene they were to shoot. Joseph also brought along the pack of cards and a lighter he used in the film – the former belonging to his Uncle Salvatore and the latter to his Father. These were objects brought from Italy to this country by real Italian immigrants and helped the actor to create his multi-layered “Danilo”. Appropriately for a story about the drama of being a part of a family and the way we mythologise things that happen within these mini tribes, this film was evidently made with a genuine sense of family, fun and collaboration. Those in the audience who were related to the actors who played in the film, or who had been extras in it themselves, spoke movingly of what an important event this film was and continues to be in their lives. 3. Finding A Way Into The Story Little Italy was the inspiration. Tony was intrigued by the idea of a hidden corner of London where the rules are different, so the story began with a sense of place. It took five years to take shape. Finding Eddie Luca as the narrator – seeing it all through the eyes of a ten-year-old boy – was the key into the story-world. 4. Discover Your Inner Actor “There’s a lot of acting involved in writing,” says Tony. “You pretend. You spend your day doing what other people gave up doing when they were twelve!” Later, when audience members lay claim to your characters and tells you so-and-so was exactly like this, that or the other member of their family, you know you’ve done something right. 5. Representation The film portrays the Italian-British community - one not often seen in British films, despite its size and reach. This is in direct contrast to the situation in the USA where there is a lot of representation of the Italian-American community on film. Tony puts this down to power in the film industry. Who makes films? They’re the ones who ultimately decide who gets represented. In the States there are lots of Italian-Americans involved in film (think Capra, Coppola, De Niro, Pacino, Scorsese, Tarantino…), but that’s not the case in this country. You could say the same thing about the Greek community, the Kurdish community, the Pakistani community - or any other community you might care to mention. 6. Story Trumps Everything Finding a community hitherto unexplored on film is a marvellous opportunity for writers old and new to find a fresh setting for universal stories with unique, often quirky details. However, story trumps everything - even good intentions regarding representation. 7. Stick Your Neck Out For Your Story Tony was not on the set much of this, his first film. That’s something that has changed over time. Now he stays with the story through to post-production. As a parting piece of advice, he encouraged writers to stick their neck out for their story. Of course the story is going to develop and change through collaboration as the production progresses, but the writer should lead that process. That’s the job of the writer. You, the writer, are the guardian of the story. Final Word My heartfelt thanks go to Nicola Gallani of Arrivederci Films for organising this event and to Tony Grisoni, Joseph Long, Ray Marioni, Tat Whalley and all the members of the Italian-British community who came along and warmed up a drab, damp Saturday afternoon. If you’d like to see “Queen of Hearts”, there’s another screening at the Italian Social Club in Clerkenwell on April 17th, 2015. Check the website of Arrivederci Films for details. I’m a veteran of London Screenwriter’s Festival. I’ve been a delegate for the last three years and will be again come this October. It’s intense, motivational and inspiring. Every year I come away laden with knowledge, insight and ideas to help me become a better writer. If there’s one thing London Screenwriter’s Festival constantly encourages us writers to do, it is to learn from each other and from role models. “If one always looked to the skies,” said Flaubert, “one would end up with wings.” Among the role models I look up to and hope to emulate is Jimmy McGovern. With “Banished”, he’s giving us a real treat. I’m enjoying it not just because it’s a great story with wonderful characters, but also because I now know enough about screenwriting technique to see how he makes our emotions soar. Take this one scene from Episode 3, which comes in at just under a minute (despite being a page and a half in Final Draft, according to my transcription). From a screenwriting perspective it’s pure genius, replete with lessons for any budding screenwriter hoping to grow wings to enable their writing career to take flight. (Minute 46:23) (Minute 47:47)

Here are five key lessons you can draw from this scene. 1. Enter a scene late and leave early The card game is already underway and we the audience arrive mid-way through the conversation. We don’t have to wait for it to warm up. It’s already reached an interesting point, which immediately draws us in. Once all the information to be conveyed by the scene has been imparted in an entertaining way, and the punchline has been delivered, we leave. James has only just begun to gloat about having won the hand by fooling Tommy into thinking he wanted the king, but the audience has seen enough to get that message. We don’t need to hang around another 30 seconds or so. In film, every second counts. 2. Drama is conflict Conflict arises on different levels. McGovern places his characters in an inherently competitive situation: a game of cards. This heightens the natural tension between the characters as a result of their different agendas. It is James who keeps us focused on this aspect of the scene, prompting Tommy three times to select a card. Tommy and Stubbins are distracted, debating the value of learning to read and write. Stubbins reveals Tommy got another convict, ‘Letters’ Molloy, to write Elizabeth a letter while he was in jail awaiting execution. This creates still more conflict, because Elizabeth now wants to know what’s in the letter. Additionally, it builds towards future conflict and creates dramatic irony through set-up and pay-off. We know Tommy’s letter was an outpouring of love and we are soon to discover that Stubbins' wife's letter is the very opposite. ‘Letters’ Molloy, “one of the most trustworthy men amongst us”, has lied. A previous scene – when Tommy wrote his last letter in prison – is paid off, while a future conflict is set up. Stubbins is going to find out the truth sooner or later… 3. Contrasting Verbal Strategies The dialogue is fresh and dynamic because each character has a different verbal strategy. Sprag’s strategy is silence. He only delivers one line, of one word, in the whole scene. Stubbins' is truth-telling. He reveals something Tommy would rather Elizabeth not know. Tommy's is avoiding the subject. He bats away all questions about the contents of his last letter to Elizabeth. Elizabeth's is curiosity. Now that it’s piqued, she wants to know what is in that damn letter. James’ is interruption. By constantly diverting Tommy’s attention back to the card game, he fools him into thinking he wants that king. All the characters have their own agenda, and they’ve all got different ways of going about getting what they want. 4. Dialogue As Action Dialogue is not about telling the story. As this scene demonstrates, it’s about revealing character, entertaining the audience, pointing to subtext and creating anticipation. The dialogue moves the story forward. Stubbins expresses his enthusiasm for learning to read and write. He wants to re-read the cherished letter from his wife, which gives him the strength to face the hardships of convict life, and to be able to write her sweet letters in his turn. In the very next scene we will learn of ‘Letters’ Molloy’s deception and we will believe it when he tells Captain Collins that if Stubbins ever learned the truth, he would almost certainly kill himself. 5. Storytelling technique The story in this scene is told with great economy in just 56 seconds. We the audience are –

A good storyteller is one who grips the audience with a multi-layered story told with brevity and humour, just as Jimmy McGovern does here. I can’t wait for Episode 4! MY CHRISTMAS GIFT TO YOU: 3rd in a series of special posts giving extended versions of the interviews for "Rejected? 3 Industry Pros Tell You: Don't Give Up!"

MY CHRISTMAS GIFT TO YOU: 2nd in a series of special posts giving extended versions of the interviews for "Rejected? 3 Industry Pros Tell You: Don't Give Up!"

MY CHRISTMAS GIFT TO YOU: 1st in a series of special posts giving extended versions of the interviews for "Rejected? 3 Industry Pros Tell You: Don't Give Up!"

|

AuthorOne of my uncles calls me, “Kim the Intrepid”. Adventures include an African revolution, questioning by the KGB/FSB and being guest of honour at a Turkmen wedding. What else would I want to do but write?

Archives

Février 2017

Categories

Tout

|

Flux RSS

Flux RSS